The DoorDash S-1 is a coming of age for the young company, where it represents the maturation of a model that has long been criticized for low margins and heavily subsidized by investor capital. But that same model has also proven almost prescient as the COVID-19 pandemic has stormed through the restaurant industry and pushed it to its limits.

Understanding the S-1 requires that we take a step back and look at what’s changed in the restaurant industry and how DoorDash fits into the broader puzzle.

The Restaurant Industry Is Still Being Hit Hard

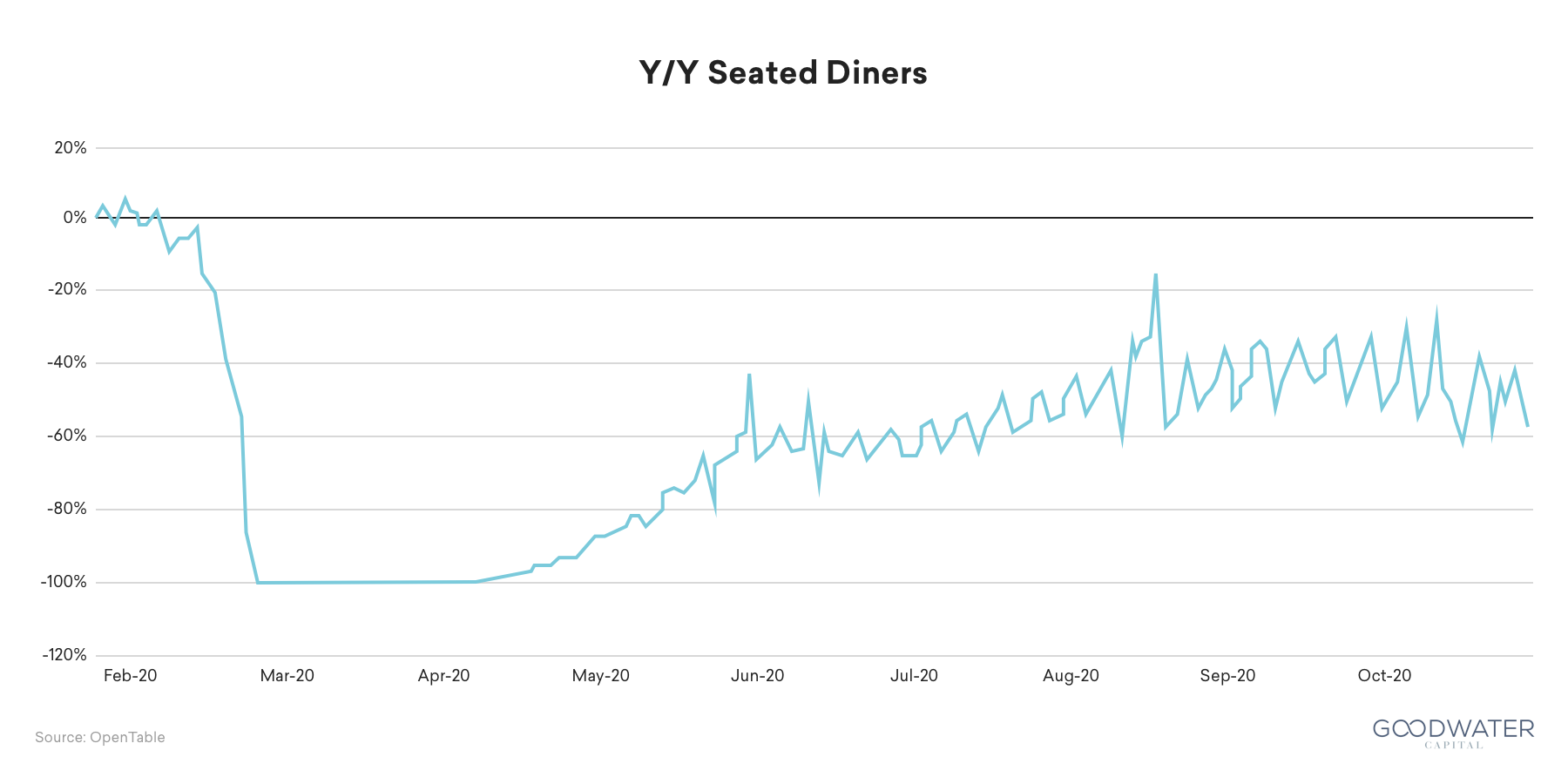

During the early part of COVID-19, a nationwide lockdown brought the restaurant industry to a standstill. While restrictions were eased through the spring and summer, new waves of infections have kept capacity limits and seating restrictions in place in many parts of the country. OpenTable data perfectly illustrates the severity of the initial shutdown and the subsequent loosening. However, as surges of COVID-19 have swept through the country, reopenings have stalled with capacity limits still enforced. Entering the winter, the restaurant industry is still down around 50-60% Y/Y with seated diners.

But Delivery Platforms Have Been a Lifeline

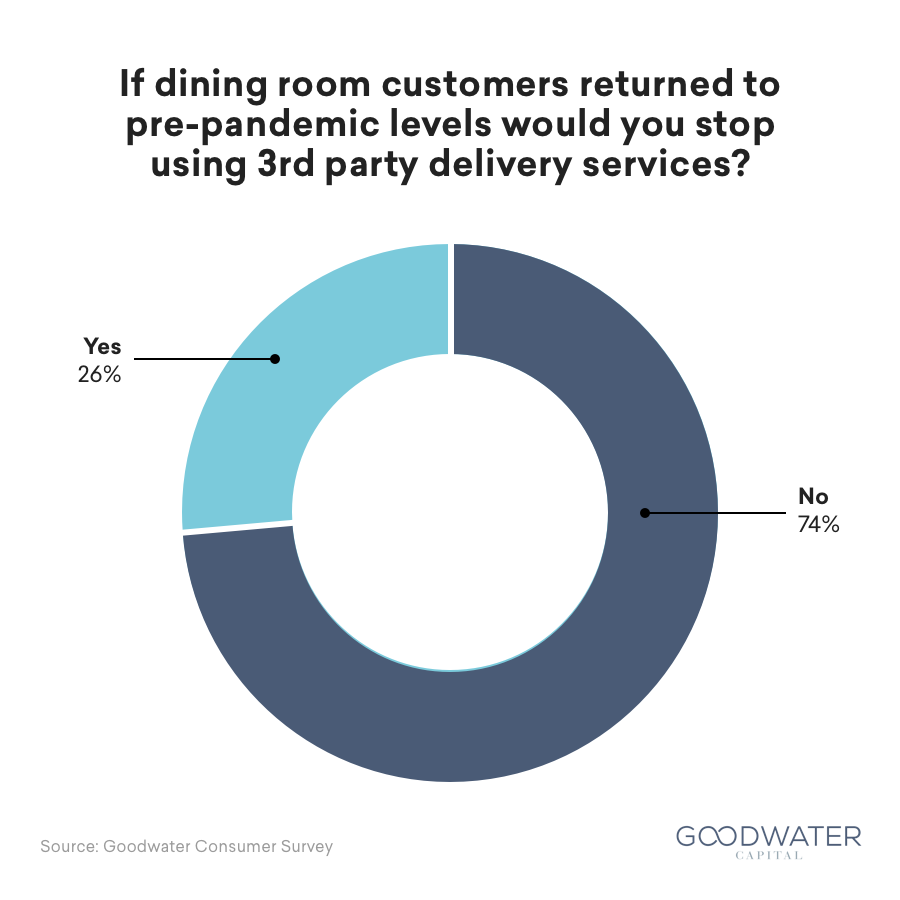

It’s against this backdrop that delivery platforms have been an essential lifeline to the industry. While there were lots of pre-pandemic negative sentiment of fees being too high, the narrative appears to have shifted: delivery platforms have been a lifeline, helping 38% of restaurants stay in business. They have been so useful that survey data indicates that even if dining rooms returned to normal, third-party delivery apps are here to stay:

Many comments from the Goodwater survey signal the pragmatism of the solution that delivery brings:

“Depending on the weather and time of day, some customers cannot dine in. They call in for delivery, it’s convenient for both the restaurant and customer. Not to mention if someone is not feeling well they normally opt for delivery.”

“We used the service before Covid because some people can’t leave their job for lunch or those that just don’t feel like or for whatever reason can’t leave home.”

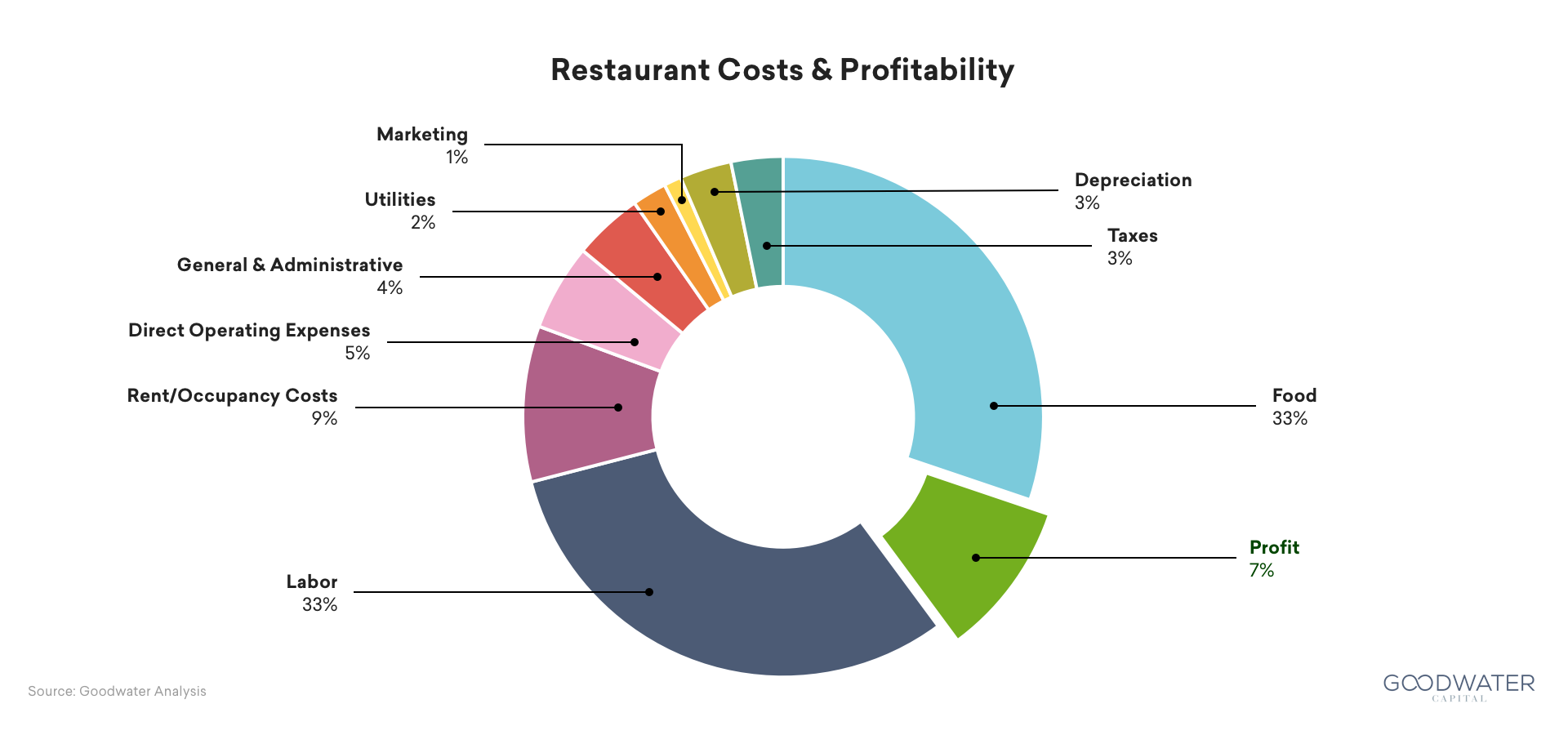

Despite the negative press around fees, these delivery marketplaces still benefit restaurants! And this makes sense, because from the restaurant perspective, many of their costs are fixed:

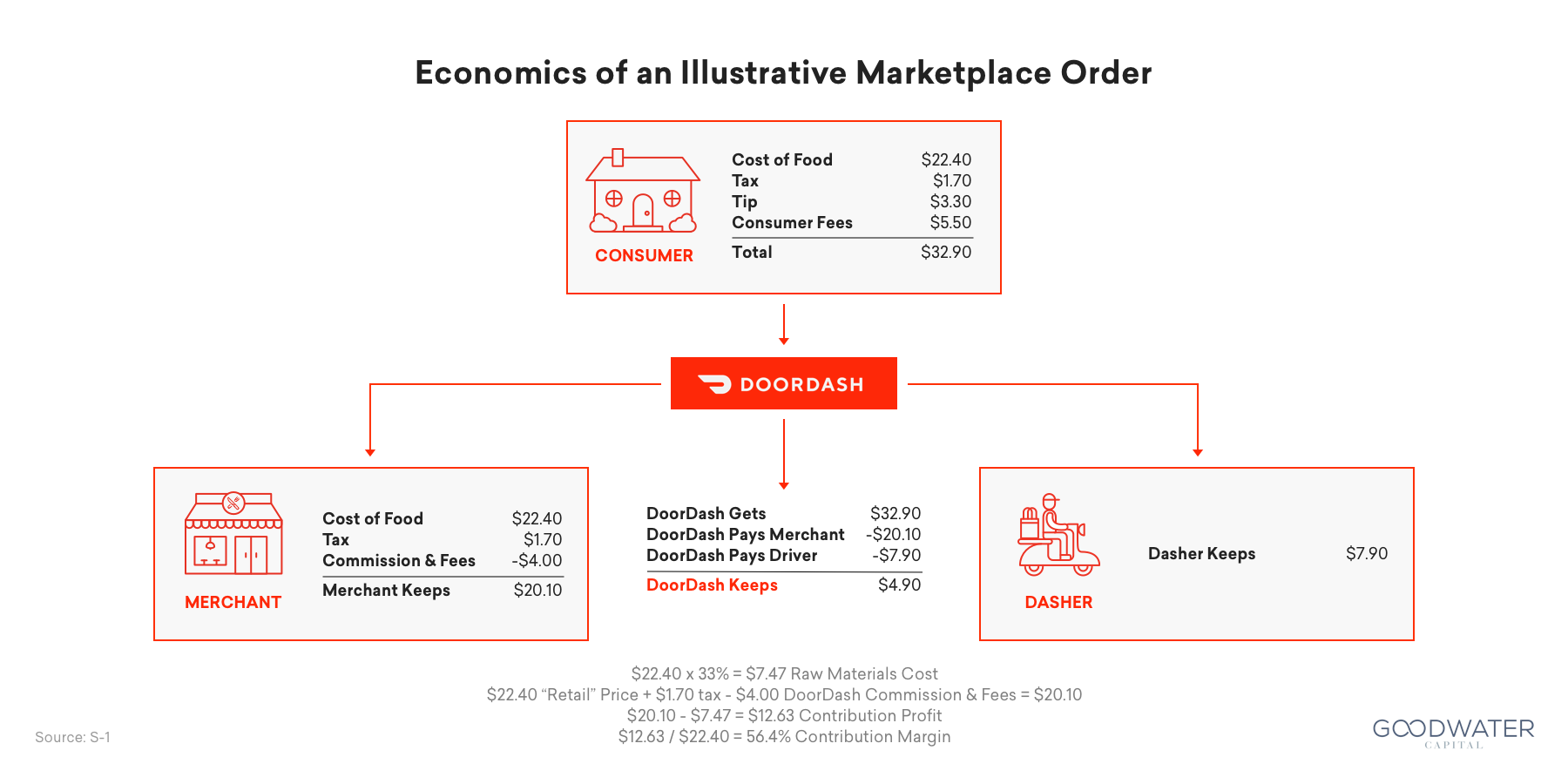

Almost everything except food costs are fixed, which means that any incremental orders are helpful to restaurants. Taking DoorDash’s S-1 example, a $22.40 order actually has a relatively healthy 50-60% contribution margin for the restaurant:

This is compared with a 67% contribution margin from a “regular” order. This ten point difference makes it difficult to run a 100% delivery business since most restaurant margins are single-digits, but it’s also hard to imagine that any well-functioning restaurant with healthy dining room volumes would turn away incremental orders from these delivery platforms.

Competitively DoorDash Has Just Done Better

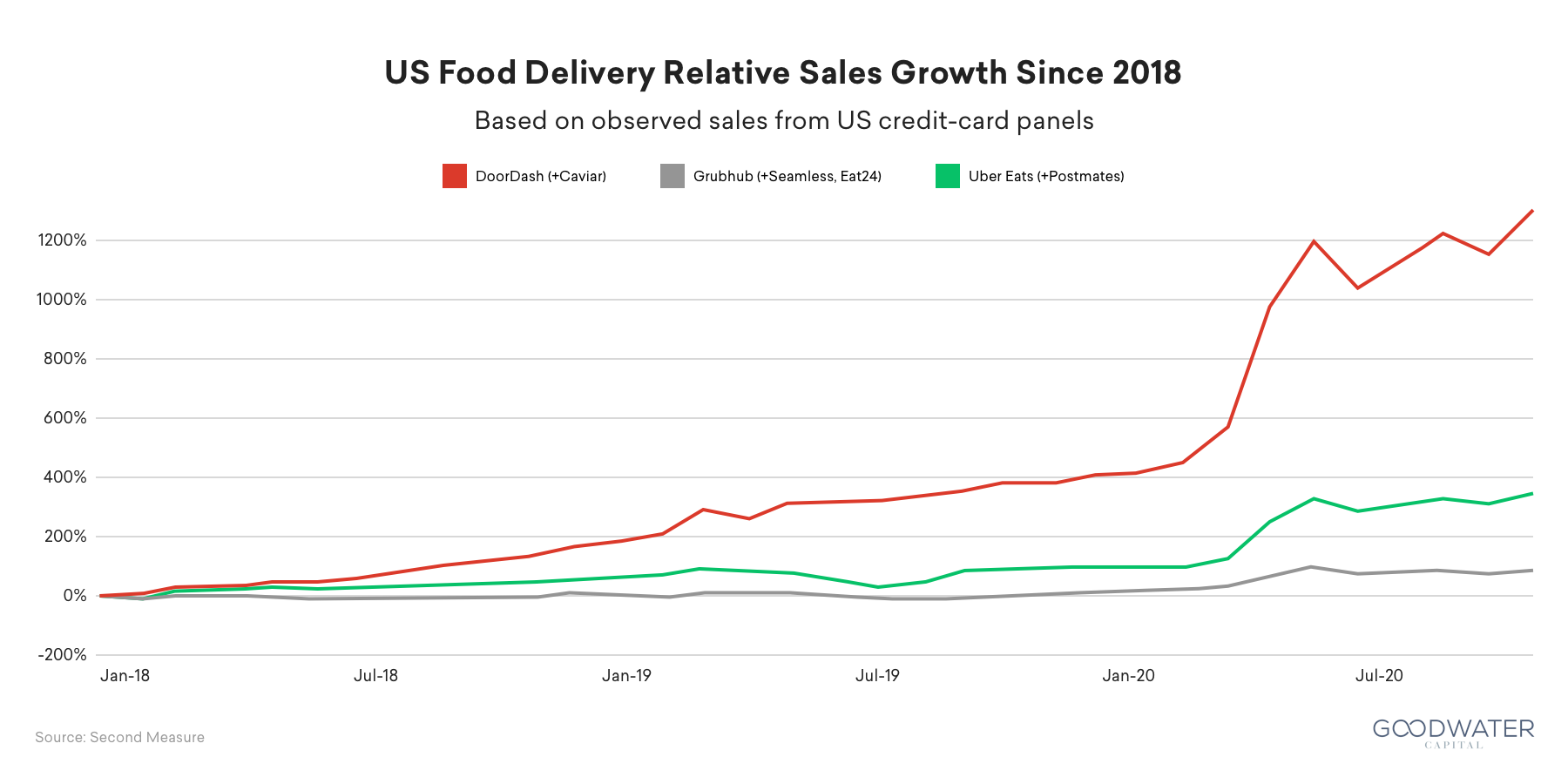

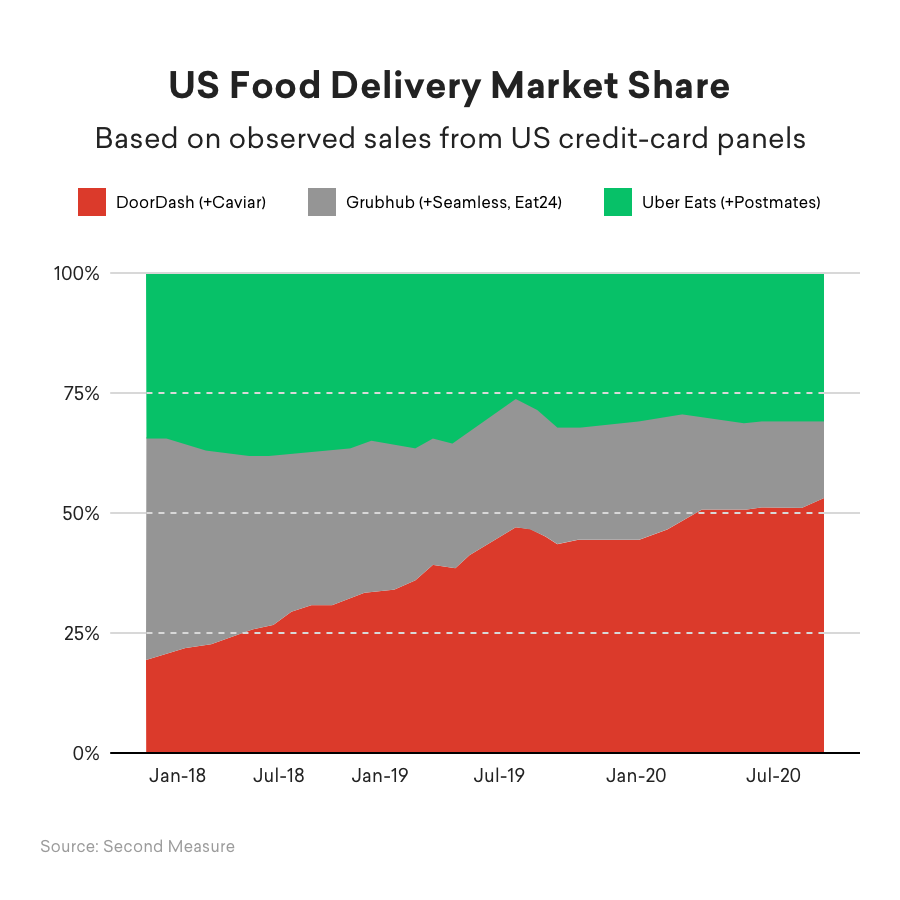

Third-party food delivery platforms have exploded since the beginning of the pandemic, and the entire industry has experienced strong growth.

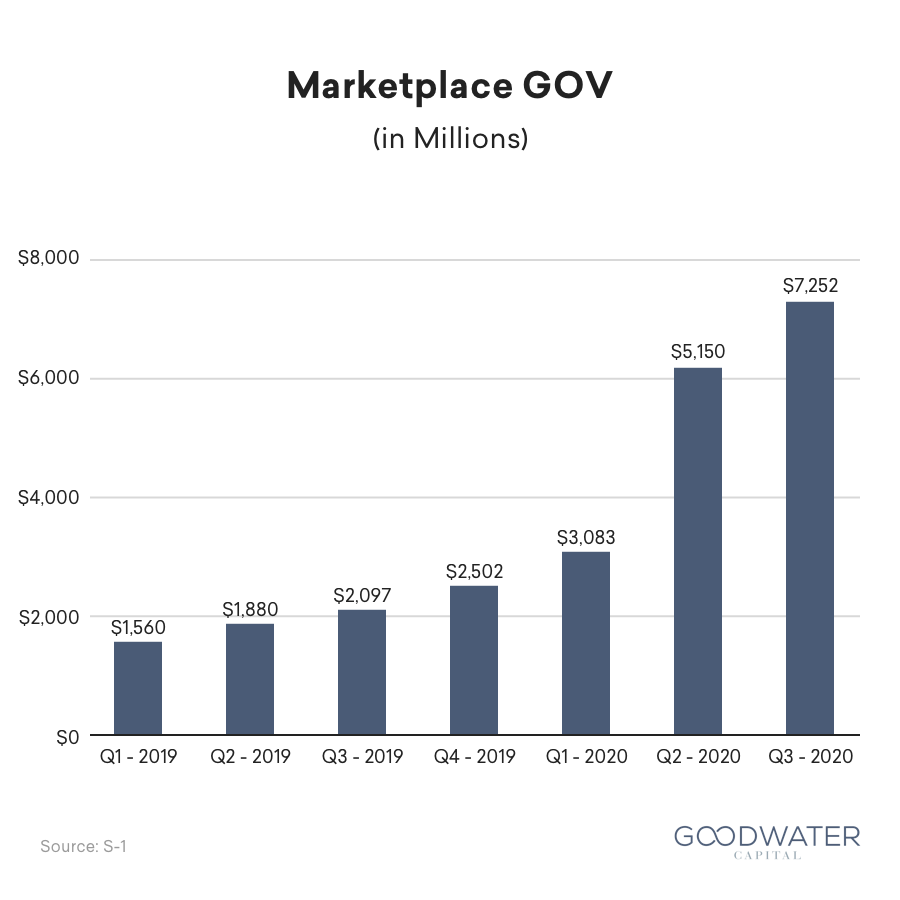

DoorDash has been particularly successful – gross order values (GOV) increased by 2-3x and continues to gain market share. In the span of 7 years, DoorDash has resulted in 390,000 merchants, 18M consumers and 1M Dashers using the platform!

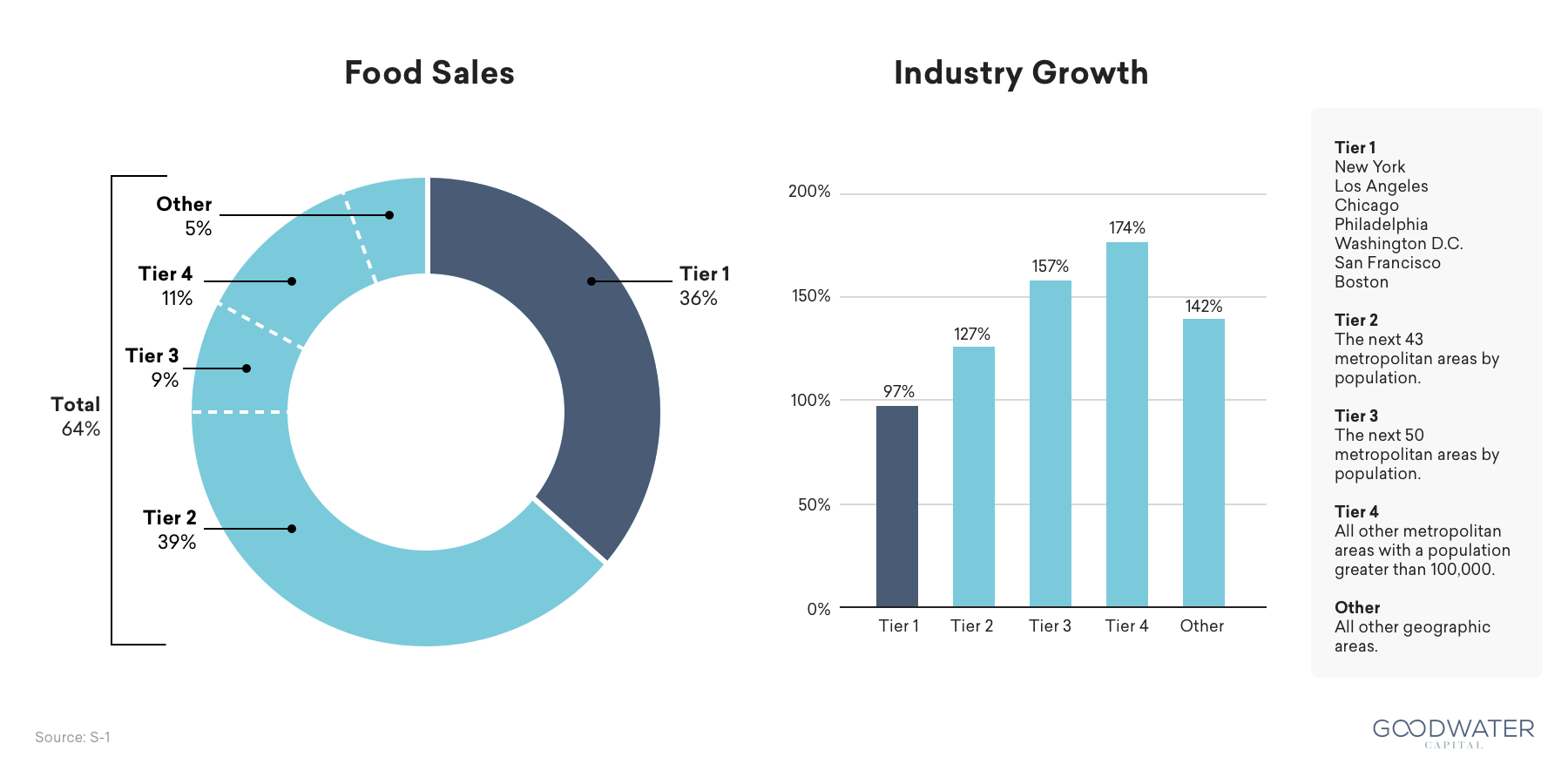

On the surface, this market was clearly dominated by Uber Eats and Grubhub. But that dominance hid the fact that these services had largely underserved the suburban and smaller metro markets. DoorDash found its initial traction in areas where the market was actually larger and faster growing.

While it is tempting to look at a market with broad strokes, the devil is always in the details. This is a good reminder that the guiding principle for every business is to: 1) look for where the consumer pain point is the highest and 2) investigate areas that competitors may have overlooked:

“We believe that suburban markets and smaller metropolitan areas have experienced significantly higher growth compared to larger metropolitan markets because these smaller markets have been historically underserved by merchants and platforms that enable on-demand delivery. Accordingly, residents in these markets are more acutely impacted by the lack of alternatives and the inconvenience posed by distance and the need to drive to merchants, and therefore consumers in these markets derive greater benefit from on-demand delivery. Additionally, suburban markets are attractive as consumers in these markets are more likely to be families who order more items per order.”

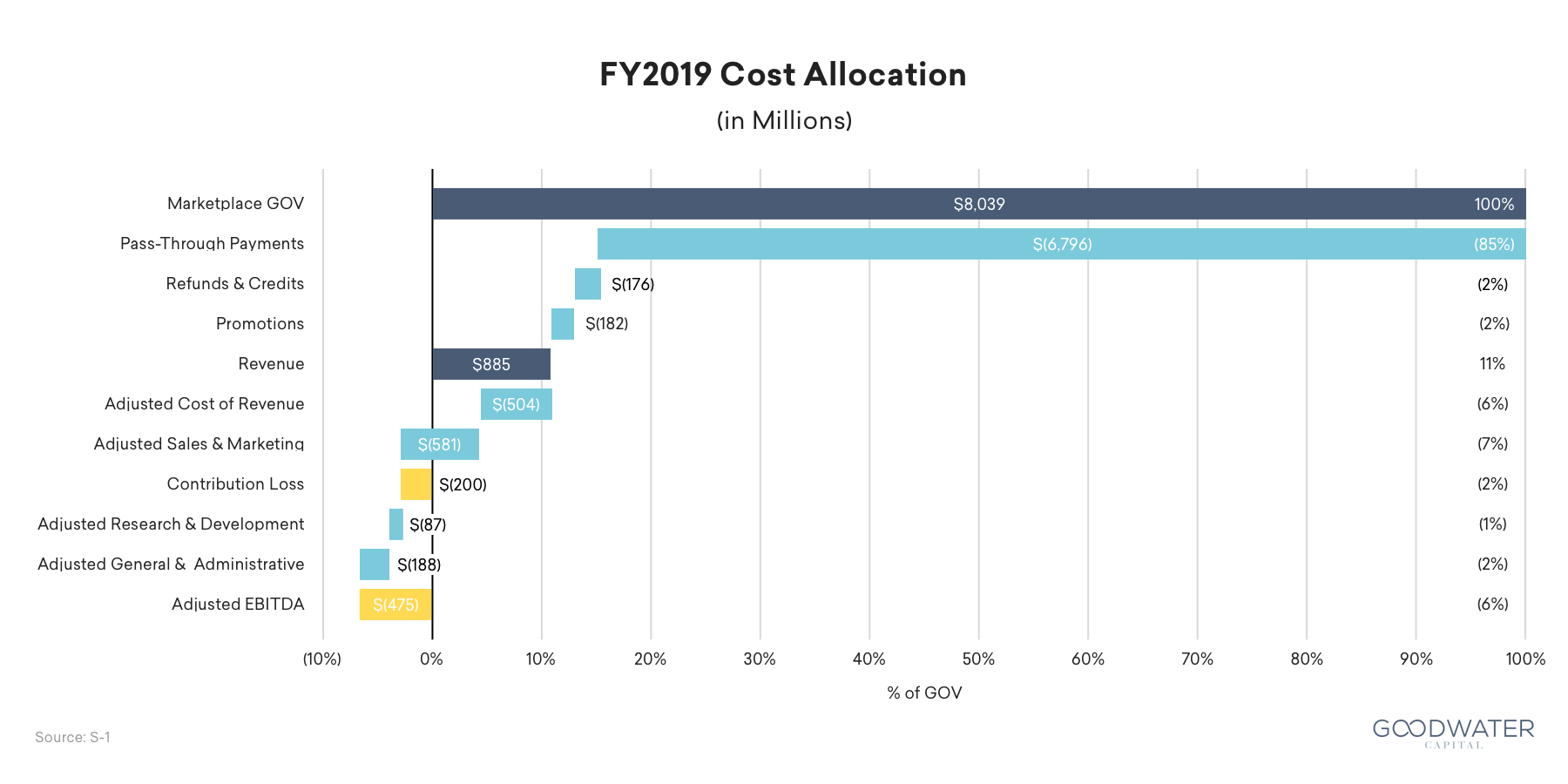

And the Business Model Actually Works for DoorDash

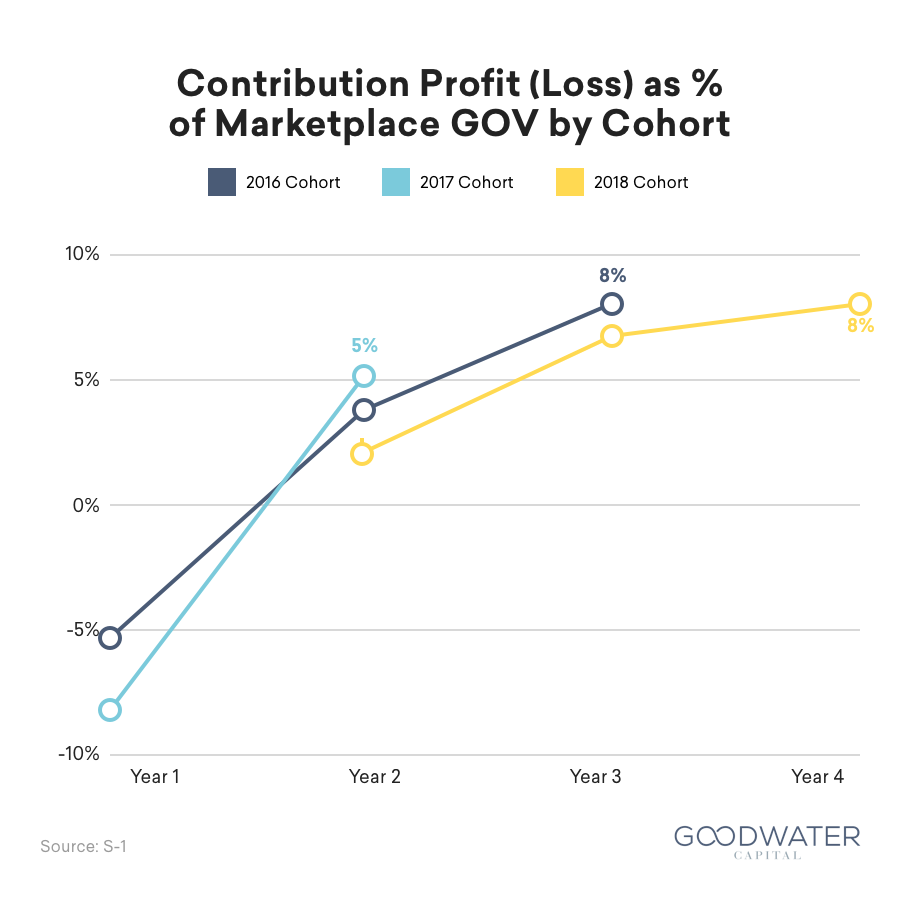

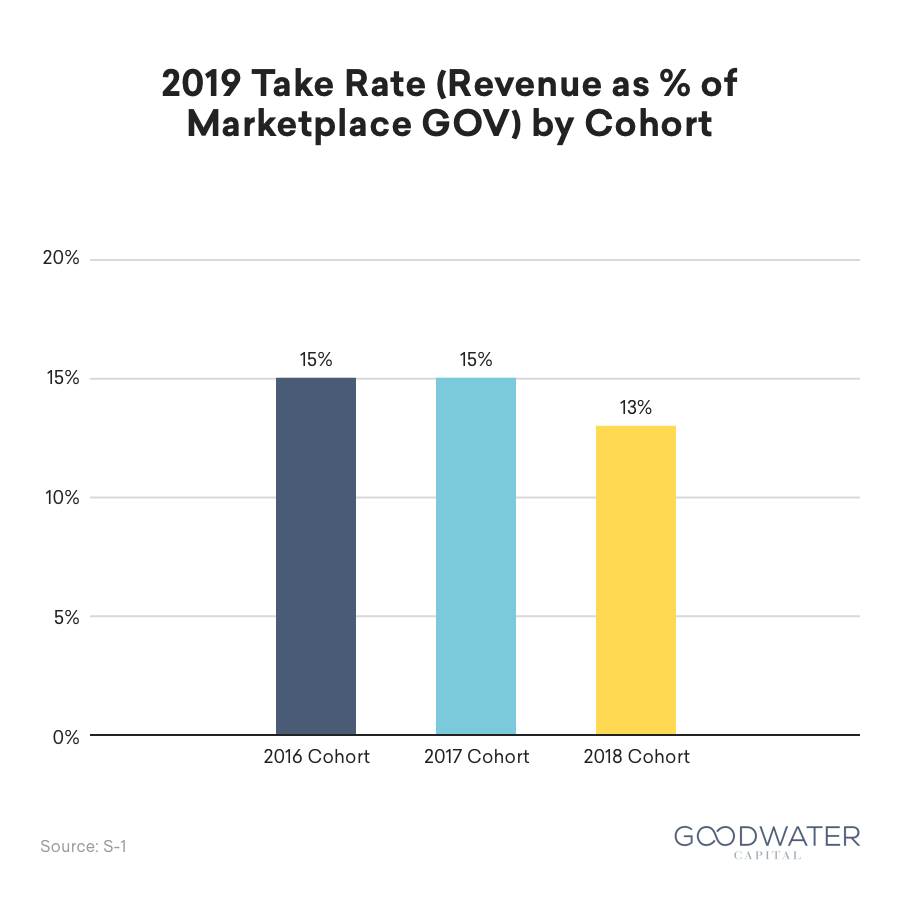

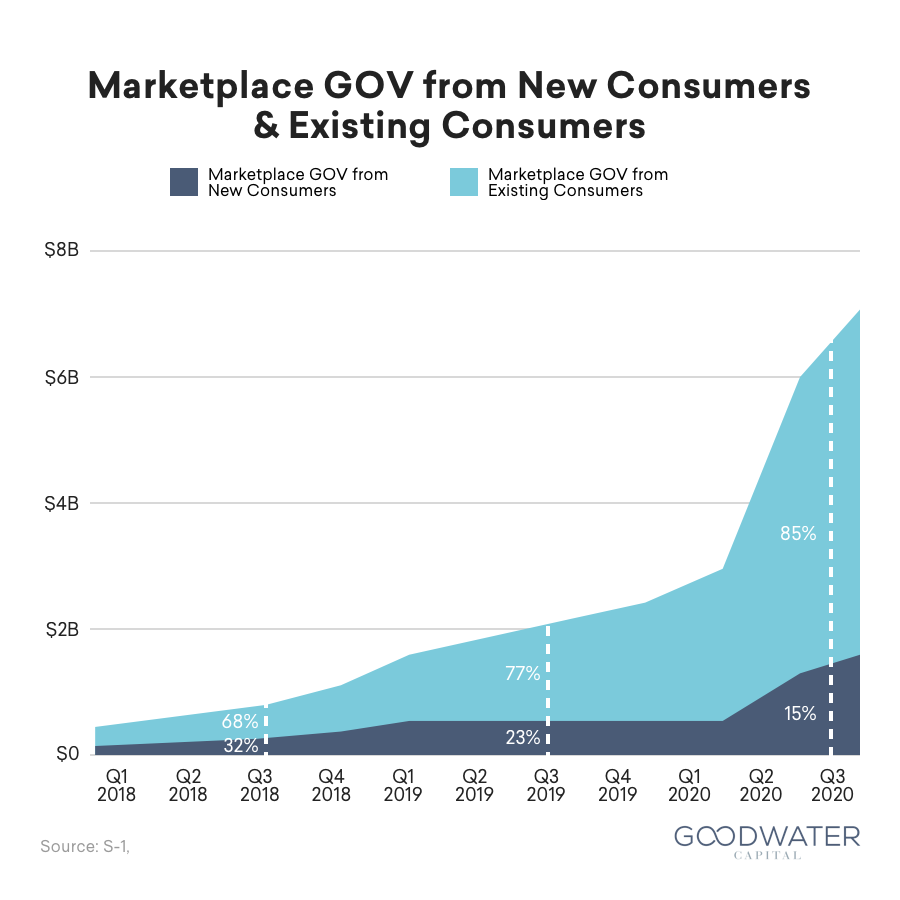

While DoorDash has been wildly successful in the market, its business model has been lambasted as being possible only with massively subsidized VC funding. What the S-1 finally highlights is how the model works for DoorDash. Since this is contribution profit from marketplace GOV, we need to back out take rate.

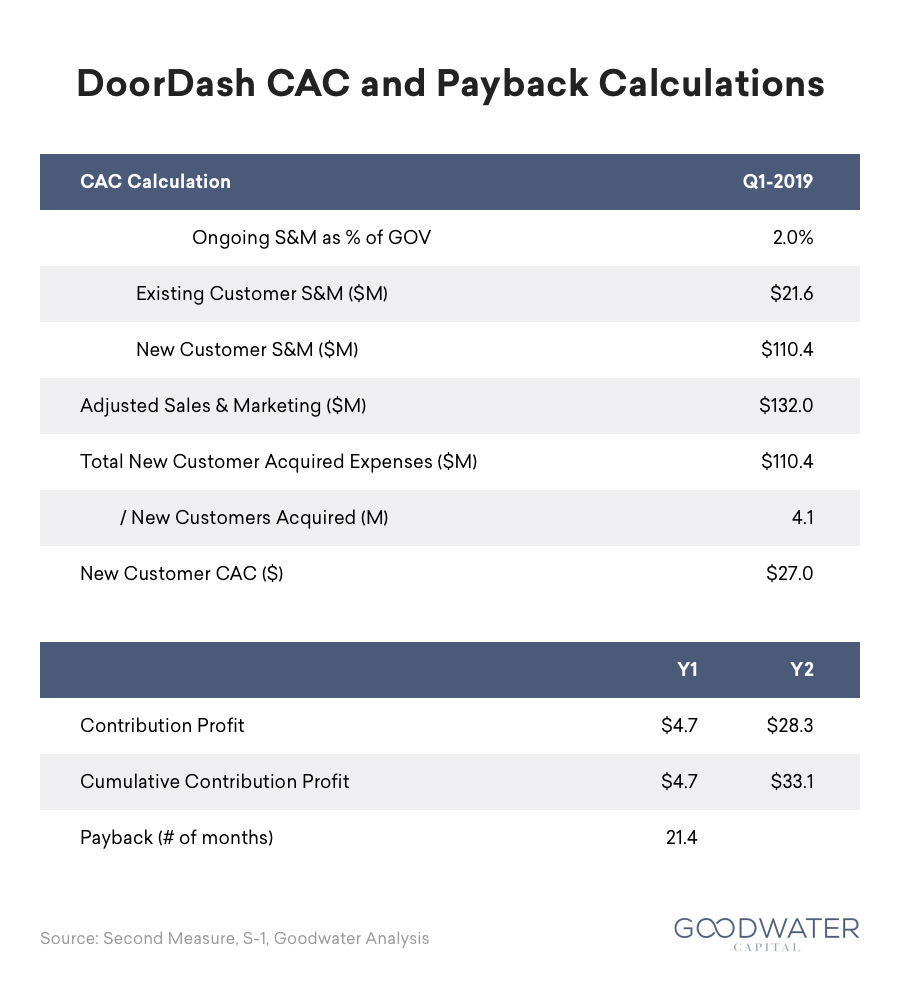

The heavy spend upfront means a -53% contribution margin in Year 1 and another 20% of revenue are being spent on ongoing sales and marketing support. As a result, CAC payback takes a little more than 2 years. Using 1Q19 data as a ballpark calculation:

However, as a cohort ages into a stable state, they begin to generate a 53% contribution margin (38% contribution margin for the 2018 cohort) — numbers that are hidden from the the large upfront spend in cost of revenue and sales and marketing needed to reach consumers, merchants, and dashers in the first place:

In a stable state, that 53% contribution margin, if we allocate ~25-30% in other operating expenses, means that DoorDash could be left with a 23-28% EBITDA margin, pretty healthy for a model that’s been heavily criticized for being unsustainable.

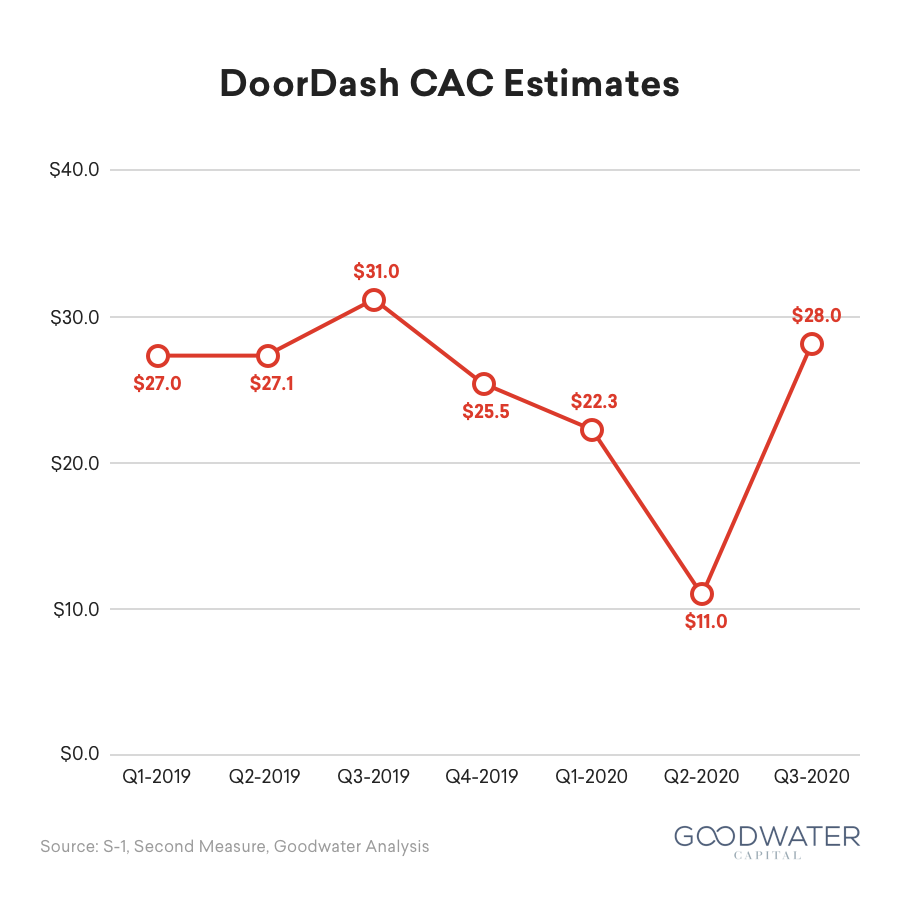

The pandemic has also lowered CACs, allowing it to increase marketing spend to previous levels:

In many ways, these same headlines focused on the lack of profitability are the same criticisms lobbed at Uber. However, just as we’ve seen there, there is a path to market rationalization and profitability.

Sustainability Lies In the Consumer

Merchants have found third-party services invaluable for their survival. Many are likely to continue to use them in general, even after the pandemic lifts — they go where the customer goes.

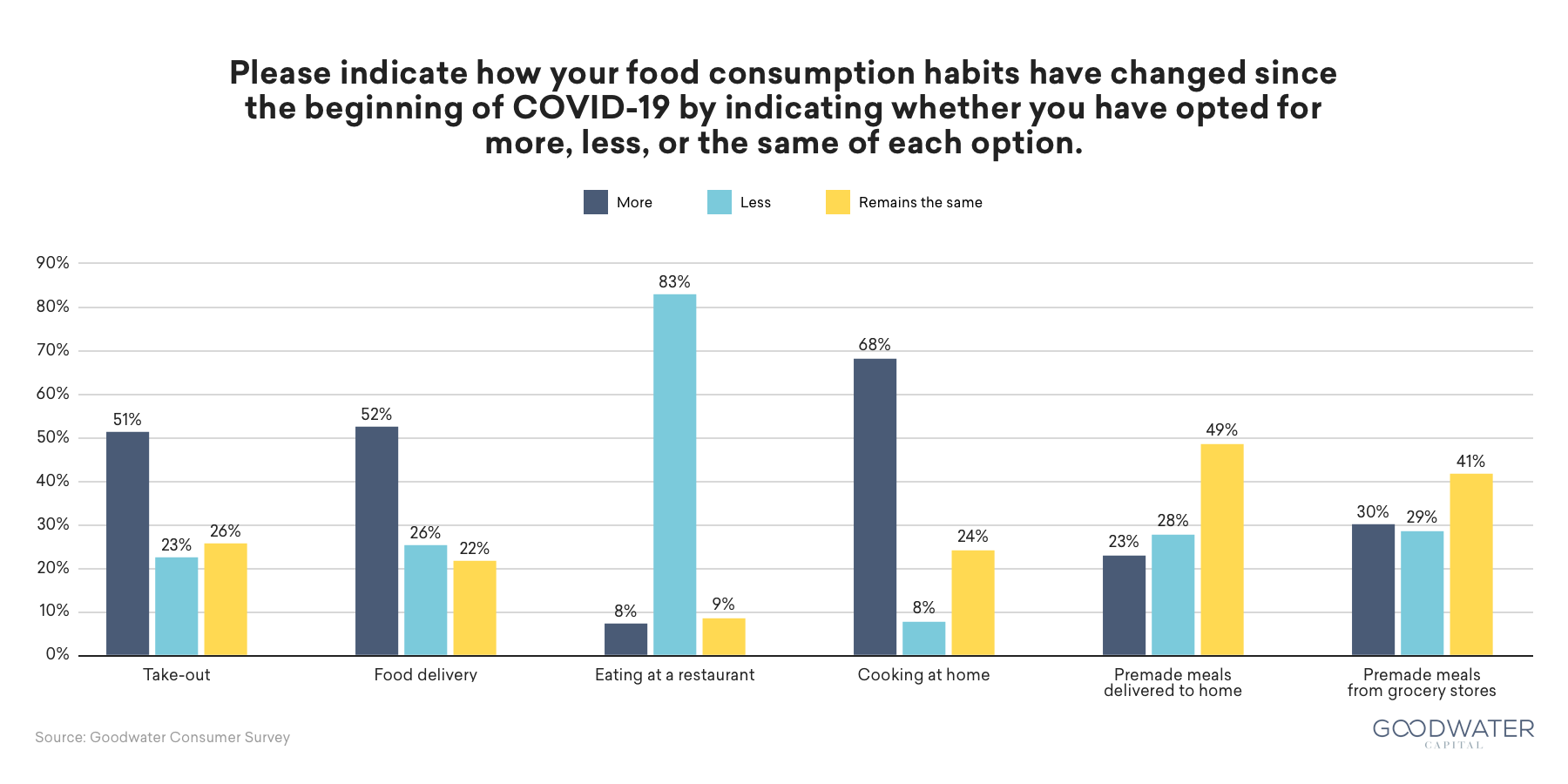

So the answer lies on the consumer side. To examine this question, consider meals as a finite pie, where each method of meal consumption is competing to occupy a share of that pie. COVID-19 effectively removed a significant competitor from the market. With the loss of dine-in options, consumers adjusted their behavior, and cooking, delivery, and takeout were clearly the ones that picked up that meal “market share”:

Third-party data also appears to confirm this share shift to delivery platforms like DoorDash:.

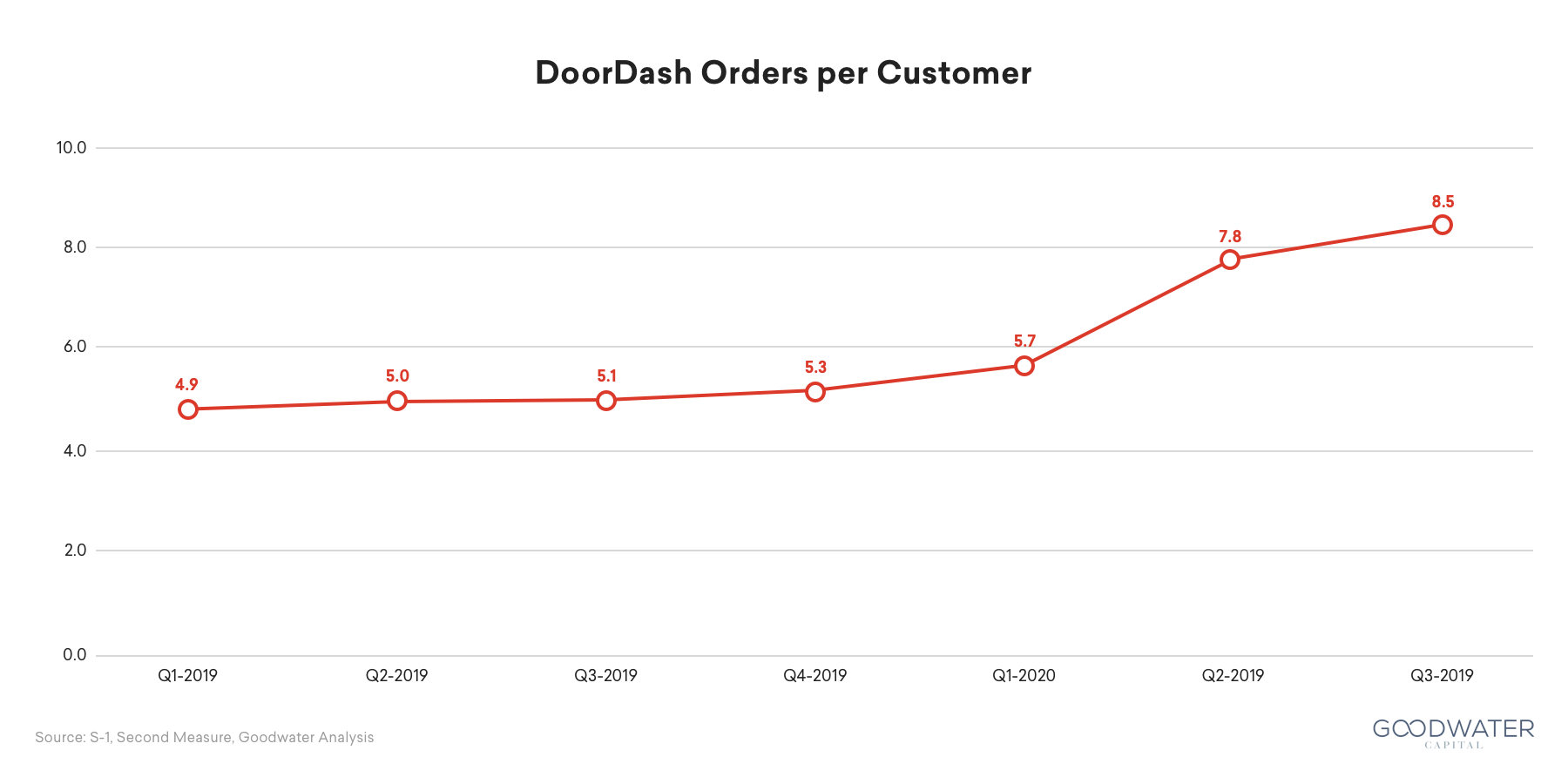

However, the data doesn’t necessarily tell us the underlying reason as to why there is order growth — it could be from a new, highly engaged set of customers, or existing customers shifting their orders from other platforms to DoorDash.

The underlying drivers are hinted at in DoorDash’s S-1 — where two things happened:

- The share of Existing Customer GOV jumped significantly

- DoorDash’s market share gains slowed significantly starting in April (see above market share chart)

The data tells us that: 1) the bulk of growth didn’t come from new customers trying the platform for the first time, and 2) the bulk of growth wasn’t from customers switching from one platform to another (ex. UberEats to DoorDash). Instead, the additional spending came from the last remaining source: existing customers’ lost dine-in meals.

But as we look ahead to the future, a reopened, indoor dining experience effectively means reintroducing an extremely compelling DoorDash competitor back into the market — an option that has always provided a compelling alternative for consumers with its ambience, convenience, and in some cases, cost advantage.

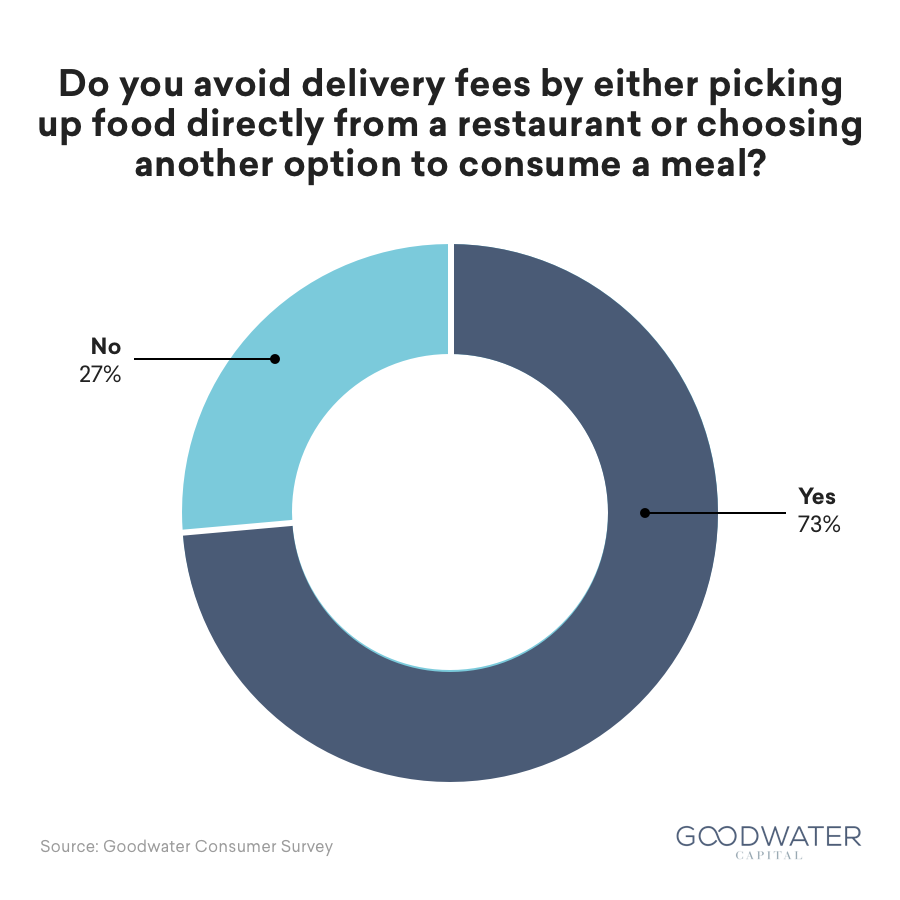

There are signs that consumers are already reaching their limits on how many more meals they can allocate to delivery — consumers have had to balance the convenience of delivery with its cost:

While still far in the distance, this meal mix shift toward delivery is likely to reverse once we can see a safe reopening. The COVID bump we see now is a bump that could reverse once dining rooms become a viable option once again.

But DoorDash Is a Sign of Things to Come

All of this analysis is just an examination of DoorDash’s interim prospects — it masks the immense long-term opportunity of the platform. It is impressive not only because of what it has been able to do, but of what might be coming in the future.

We started with Marketplace 1.0 models like eBay or Craigslist, that simply digitized the existing transactions, but ultimately left most of the details to the participants, satisfied with providing people with the initial connection. What we saw with marketplaces like Airbnb and Uber was an extension of that, using technology to provide a layer above that, giving each marketplace participant more robust software, orchestrating millions of marketplace participants and giving individuals the ability to just tap a button to start their own businesses.

But what we’re seeing now is an even broader expansion of these platforms. What is so magical about DoorDash is that, using software and the internet, it not only adds a dimension of complexity coordinating three separate sides of a market (consumer, restaurants, and dashers), but also gives them everything needed to run an inherently complex business – including queuing, menu design, group orders / catering, and CRM.

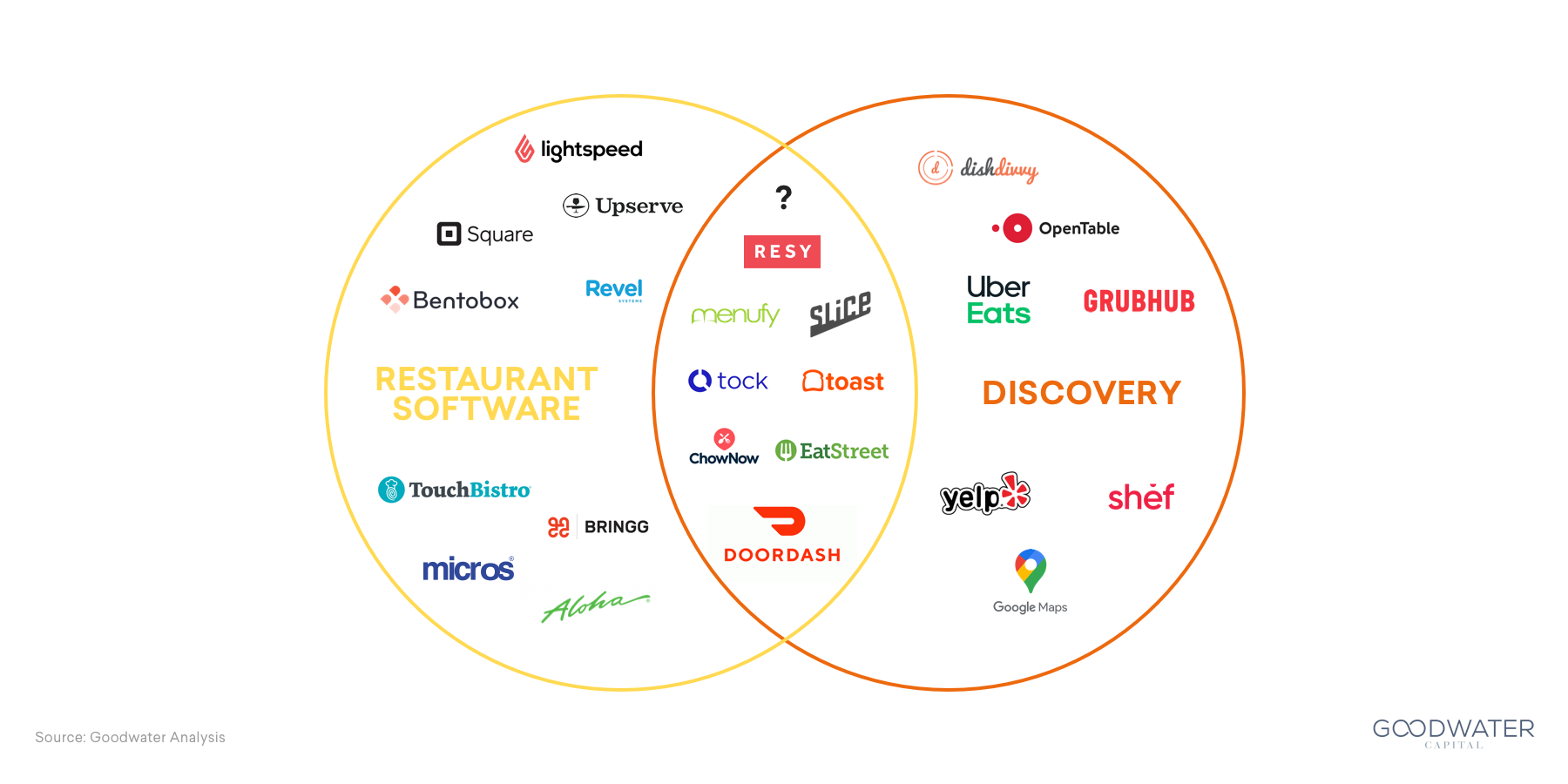

Software and the internet has allowed an entire organization to plug-in and potentially run an entire business off of just the platform. SaaS and marketplaces are increasingly colliding together:

- Toast, a SaaS point-of-sale solution, introduced a consumer-facing app, Toast Takeout, for consumers to search for local restaurants.

- Slice, a solution focused on pizzerias, started with both SaaS-functionality and a consumer facing app for restaurant discovery.

- ChowNow, a SaaS online ordering system, also has a consumer-facing app to help consumers discovery restaurants.

- Menufy offers online hosting of a restaurant website and online ordering with an automatic listing on the Menufy website.

- EatStreet, an online-ordering SaaS solution for restaurants, has always had its own consumer facing app.

- Tock, a restaurant reservation platform, launched Tock to Go, allowing restaurants to offer online ordering.

- Resy, a restaurant reservation platform, is planning on launching Resy at Home, to support online ordering.

With its massive size, constant competition, limited resources, and massive COVID dislocation that has roiled the industry, perhaps it makes sense that the restaurant industry is one of the first categories where this convergence is occurring. Viewed in that context, the DoorDash vision really isn’t so crazy:

“We have already started to serve merchants in other verticals, such as grocery and flowers, but we are still in the very early stages of expanding beyond food. We have just begun our journey and have ample opportunity for continued success in local logistics across verticals and geographies. Our ambition is to empower all types of local businesses, from single proprietors to franchisees, convenience stores to grocers, and florists to pharmacies.”

This is the greatest takeaway from the DoorDash filing: that we’ll continue to see technology “democratize” businesses, tailoring solutions that enable them to focus on their core competencies, and push the boundaries of empowering them towards success.