What if having less money makes you build a better business?

During a fireside chat between Goodwater Managing Partner Chi-Hua Chien and Tinder Founder Sean Rad, they explored this counterintuitive insight through Tinder’s remarkable journey from a 24-hour hackathon to a $2 billion ARR business. They offer a standout case study in constraint-driven innovation, which is more relevant than ever in today’s capital-efficient environment.

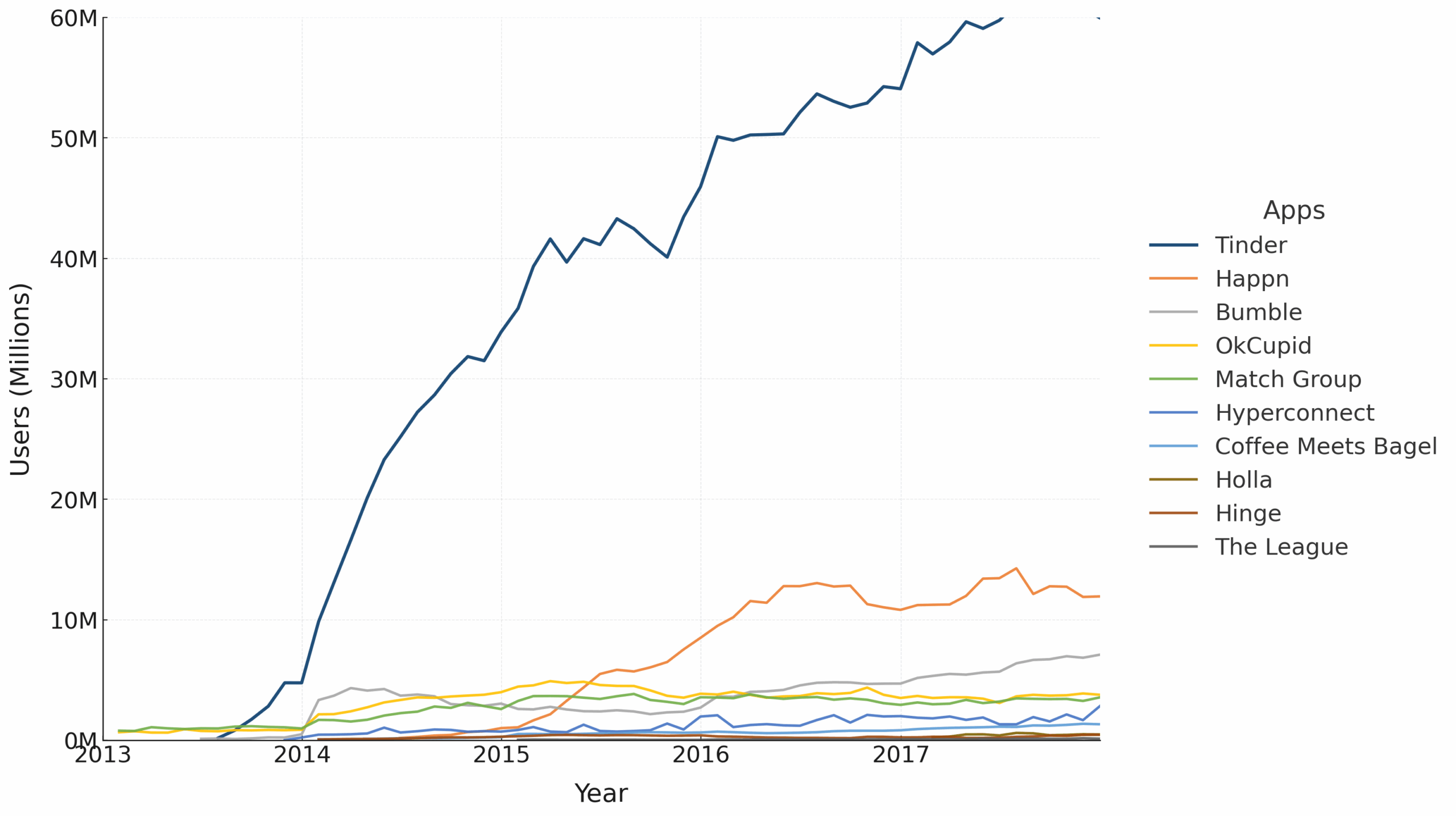

The numbers tell a remarkable story. While competitors burned through hundreds of millions, Tinder achieved profitability on just $30 million in total capital. With 150 employees generating $800 million in revenue, that was over $3 million per employee versus the industry standard of $300-500K. Tinder didn’t just build differently, they built better.

Here are five lessons from Tinder’s constraint-driven playbook that every founder should understand.

Chi-Hua Chien and Sean Rad’s fireside chat at Goodwater’s annual CEO retreat.

1. Less Capital Forces Better Product Decisions

Tinder’s most iconic feature almost didn’t exist. The swipe wasn’t part of the original product, it emerged because the team couldn’t afford to get product decisions wrong. With limited engineering resources and systems crashing nightly, every feature required brutal prioritization.

The team introduced a prioritization matrix that scored every potential feature against core business metrics. Engineering, design, product, and marketing would debate and rate each idea, and the average score decided what was built. No politics, no pet projects, just data-driven choices.

“We had such a high bar before we released something that a lot of that iteration was happening internally,” Sean recalled. “By the time it actually reached our users, it was so thoughtful that we had a high hit rate.”

The swipe came from obsessive user observation. Team members noticed users repeatedly trying to touch and drag the interface. However, convincing engineers drowning in technical debt to build this required passing their rigorous prioritization process. That discipline meant that when features launched, they worked.

The constraint advantage: Without money to experiment endlessly, Tinder developed a systematic approach to product development that dramatically increased their success rate.

2. Growing Without a Marketing Budget: The Art of Product-Led Growth

When offered access to 20 million email addresses from Match.com’s shuttered properties, Tinder said no. The reasoning was simple but profound: growth had to be organic within tight networks, earned through product quality rather than purchased through marketing.

Instead, Tinder pioneered what would later be called product-led growth. Their ambassador program scaled to 130 representatives across 30 countries, but it started with a single insight. Romance is inherently viral; when you meet someone, you tell your friends.

The team discovered a magic number: 20,000 users. In market after market, once they hit 20,000 users in a region, word-of-mouth would take over and drive exponential growth. The challenge was reaching that tipping point without paid marketing.

Their solution was brilliantly analog. At USC, they moved a 2,000-person birthday party to a new location, hired bouncers, and made Tinder the price of admission. Students had to show the app on their phones to enter. The next morning, hungover college kids opened this mysterious app and started swiping. Density achieved and network effects kicked in.

“We were our own ambassadors,” Sean emphasized. “If we were at a restaurant, we would try to get the waiter, the waitress, everyone around us using the product. Every single user mattered.”

The constraint advantage: By refusing to rely on paid acquisition, Tinder built features and experiences that users genuinely wanted to share. Their cost of acquisition remained near zero while competitors spent millions on marketing.

Tinder’s explosive growth by MAU (mobile only) from 2013 through 2017.

3. The Power of Saying No: How Constraints Create Focus

“There’s really only three things an organization at a given time can really, in a unified sense, understand.”

This philosophy drove Tinder’s product development. While competitors built features in parallel across multiple teams, Tinder insisted the entire company focus on a maximum of three initiatives. When employees could draw a clear line from their daily work to company goals, magic happened.

The discipline extended to team size. “Every time we would add someone to the team, it would slow us down, it would create drift, it would add more cooks in the kitchen.”

This wasn’t arbitrary minimalism. It reflected a fundamental belief that people don’t solve problems, focused thinking does. When Twitter’s transformation under new leadership removed two-thirds of staff and saw productivity increase, it validated what Tinder had practiced for years.

The constraint advantage: Resource constraints forced extreme focus. While competitors spread efforts across dozens of initiatives, Tinder’s concentrated approach meant they executed fewer things exceptionally well.

4. Turning Limitations into Product Innovation

Tinder’s monetization strategy emerged from a counterintuitive insight: the best revenue features actually improve the product ecosystem. When some users swiped right on everyone, it degraded the experience for others. The solution? Limit daily swipes for free users. What started as an ecosystem protection mechanism became their first major revenue driver.

Super Likes followed the same pattern. Users wanted to express heightened interest, but unlimited Super Likes would render them meaningless. The solution was elegant – one free Super Like daily, with subscribers getting five. The scarcity created value. Users wondered: “Did that person use their one free on me?”

The team discovered that 50% of their revenue came from optimizations, not new features. They pioneered “breadcrumbing,” which was when you presented premium features at moments of maximum value rather than overwhelming users with a feature list. When you ran out of Super Likes, that’s when Tinder offered more. Context created conversion.

The constraint advantage: Unable to hire large sales teams or build complex payment systems, Tinder made monetization intrinsic to product value. Premium features enhanced rather than gated the experience.

5. Building a Championship Team on a Shoestring

“Passion won over experience nine times out of ten.” Sean shared.

When you can’t match Silicon Valley salaries, you hire differently. Tinder’s co-founders included a party promoter and an actor who taught himself to code. Their CTO had never seen scale. But they all shared one trait: obsession with the product.

Interview questions were simple but revealing. “One through ten, how passionate are you about this role?” Anything 10 or below meant not enough passion. The team wanted people seeking greater than 10, those who couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

“If you have an extremely high bar, you have an extremely honest, open, transparent, semi-abrasive culture, but it’s all in the interest of the company and the user, it encourages people to leave,” Sean noted. This natural selection meant those who stayed were truly committed.

The constraint advantage: Budget limitations attracted builders who chose mission over money. This created a culture of ownership that well-funded competitors couldn’t buy their way into.

The Lasting Impact of Constraint-Driven Innovation

Tinder’s story challenges the common “growth at all costs” narrative. By treating constraints as features rather than bugs, they built a fundamentally different kind of business. Every constraint forced an innovation. Every limitation demanded creativity. Every restriction reinforced discipline.

As capital markets tighten and efficiency returns as a watchword, Tinder’s playbook becomes essential reading. The question for today’s founders isn’t how to overcome constraints, it’s how to embrace them as your greatest competitive advantage.

Key Takeaways for Founders

- Prioritize ruthlessly: Build fewer features that truly matter rather than everything users might want.

- Make product quality your growth engine: When marketing budgets are limited, excellence becomes your distribution.

- Use constraints to improve product-market fit: The best monetization features enhance rather than restrict user experience.

- Hire for mission alignment over résumé: Passionate generalists often outperform experienced specialists.

- Maintain startup discipline at scale: The habits formed under constraints become sustainable advantages.

The most successful consumer businesses of the next decade won’t be those with the most capital, they’ll be those who transform constraints into catalysts for innovation. At Goodwater, we’ve seen this pattern across our portfolio: the companies that achieve extraordinary capital efficiency early tend to maintain that advantage as they scale.

Your constraints might feel limiting today. But as Tinder proved, they might also be the foundation of your next billion-dollar breakthrough.

For more insights on building capital-efficient consumer businesses, visit goodwatercap.com/insights. To connect with our global team about your Series A-C journey, reach out at info@goodwatercap.com.